Climate change, a major source of uncertainty across Central Asia

A sense of anxiety looms large in Barsem, a small village in Tajikistan’s Pamir mountains. Just two years ago, triggered by sudden rainfall and strong snow melting, a powerful mudflow devastated the village, leaving over 82 families without homes, cutting the local power supply for weeks, and disrupting the country’s only international transit route with China, the “Pamir Highway.”

Such disasters are frequent across Central Asia. In Tajikistan, as much as 36 percent of the country’s territory is under threat from landslides. Kyrgyzstan is prone to avalanches: between 1990 and 2009, the country had over 330 avalanches.

Barsem villagers walking on steep and dangerous slopes after a devastating mudflow destroyed the main walking roads. Photo credit: World Bank.

In these remote areas, the threats from mountain hazards are exacerbated by existing conditions of poverty, insufficient infrastructure and poor resources.

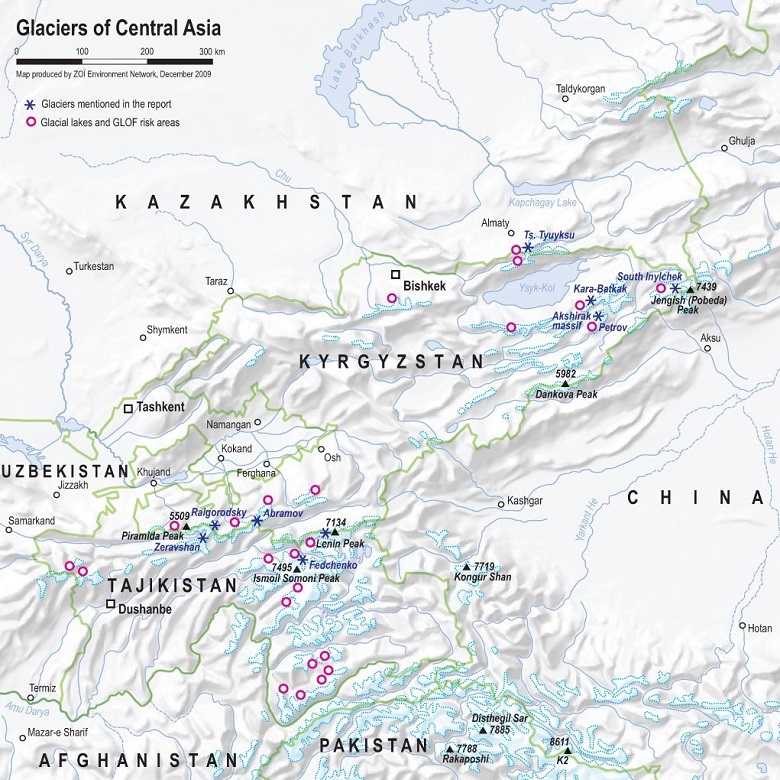

The region is also expected to see an increase in extreme weather events in the coming decades. By the end of the century, temperatures in the Central Asia region will rise by up to 6 degrees Celsius, leading to the disappearance of more than one third of glaciers from Central Asian mountains by 2050, putting nearby communities at greater risk and rolling back hard-won development gains.

By 2050, up to one third of the glaciers across Central Asia are predicted to disappear entirely, dramatically raising the risk of sudden floods from glacier lake outburst. (ZOI Network)

Anticipating disaster shocks, fostering resilience

To help countries to adapt to a riskier future, the Central Asia Hydrometeorology Modernization Project (CAHMP) is bolstering weather forecasting and early warning efforts in the region. These efforts are particularly important for Tajikistan and the Kyrgyz Republic, two of the most disaster-prone countries in the region with mountains covering more than 90 percent of their geography.

Funded by the World Bank and the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR), this $28 million investment focuses on strengthening hydrometeorological services and generating further climate-related risk information that the region is lacking.

The project provided cutting-edge technical equipment – such as modern workstations, automated observation networks, access to satellite data and numerical weather prediction – coupled with specialized trainings for participating agencies.

Because of these improvements, the forecast accuracy in the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan increased by 20 to 30 percent. With access to more accurate risk information, countries can better anticipate extreme weather events and take timely action, such as organizing evacuations for at-risk communities, putting in place protective measures and minimizing potential losses.

Rising temperatures mean that mountain glaciers are melting at unprecedented rates in Central Asia, affecting freshwater supplies downstream. Mountain communities, however, also have a wealth of knowledge and strategies accumulated over generations, on how to adapt to climate variability and other related shocks.

In the long term, decision-makers can also better plan significant infrastructure investment projects, something particularly salient in Central Asia, where aging infrastructure is gradually deteriorating from insufficient maintenance and repeated exposure to natural hazards.

Better climate information will also benefit sectors such as agriculture, which is frequently exposed to extreme weather events.

For farmers, accurate predictions of growing season, rainfall patterns, and potential hail or storm can help boost productivity and increase incomes. This is especially the case for countries like Tajikistan, where more than 60 percent of the population is solely dependent on agriculture as a source of livelihood.

Both Tajikistan and the Kyrgyz Republic have made tremendous strides in reducing poverty - from 75 to 80 percent few decades ago to below 35 to 40 percent today. Yet the challenges of a changing climate threaten to push mountain communities back into poverty without critical investments in resilience.

As the world today celebrates International Mountain Day, it is important to reflect on how to better care for these important landscapes and protect lives of the communities like in Barsem who call them home.