By Brenden Jongman, Dimmie Hendriks and Ted Veldkamp

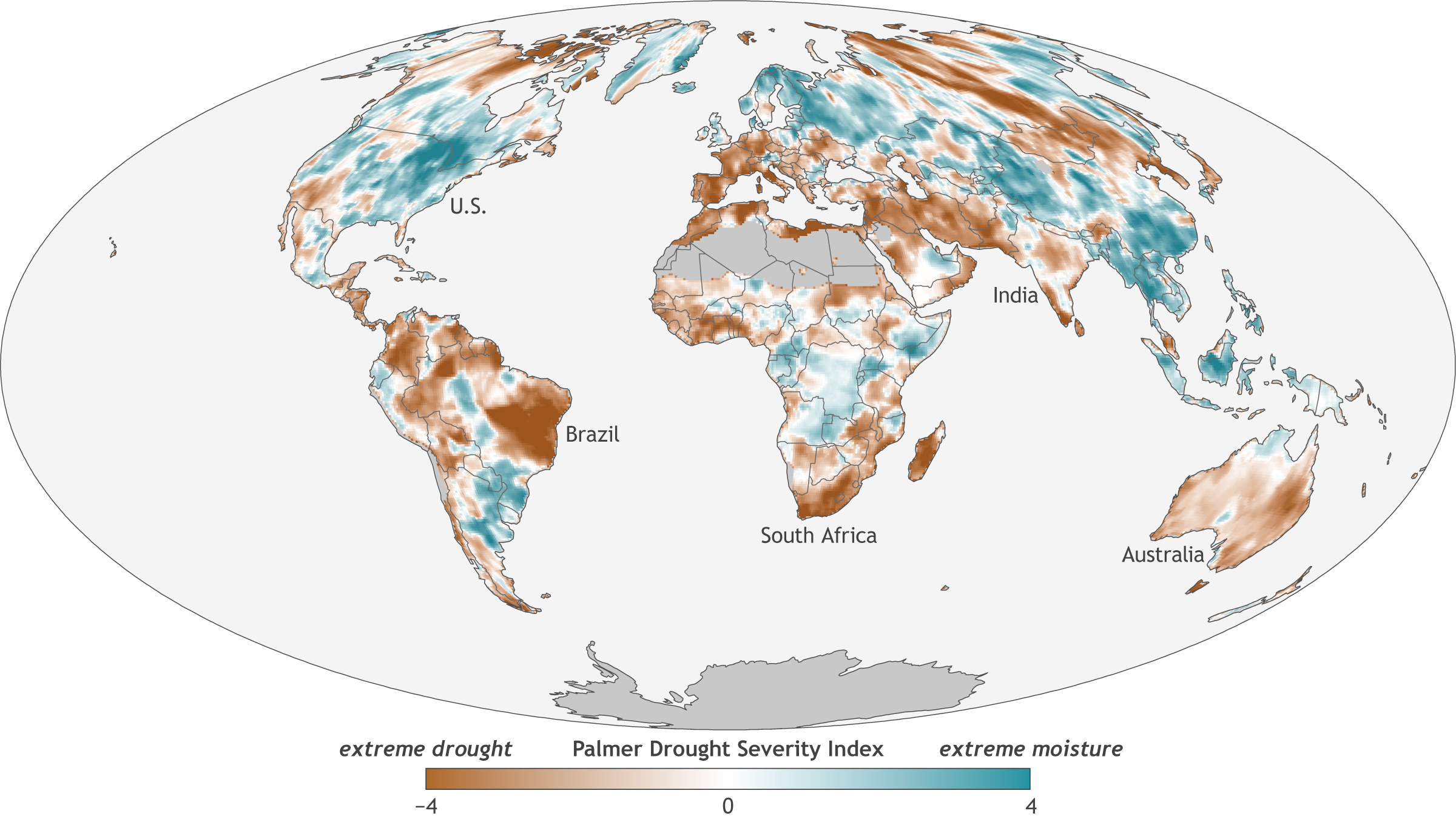

Droughts are among the most far-reaching and yet least understood among natural hazards. There is an increasing need for more accurate assessment and monitoring of drought hazards and impacts, to support decision-making on drought risk reduction, risk financing and disaster response. In the past few years alone, countries like India, South Africa and Malawi have been severely impacted by droughts that affect food supply, agricultural income, employment opportunities, drinking water facilities and energy production.

Global drought patterns in 2017. Credit: NOAA

With the support of the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR), the World Bank worked with a consortium of partner organizations to develop a new guidance document on drought hazard and risk assessment and an accompanying online Catalogue of Drought Hazard and Risk Tools. These new tools will help governments, development organizations and professionals prepare and carry out accurate drought risk assessments for a variety of purposes.

The guidance document was presented and piloted during the workshop “Dry, drier, drought” that took place at the World Bank in March 2019 and was facilitated by guest speakers from Deltares, the University of California at Santa Barbara and the Institute for Environmental Studies, VU university Amsterdam.

“This is an excellent reference document for us when starting up risk assessments in drought prone countries” - Participant of “Dry, Drier, Drought” workshop at the World Bank in March 2019

Drought risk assessments can have very different purposes and contexts. For instance, they can be conducted as part of a regional or national scale exploratory assessment of historical or future natural hazards and risks. In contrast, they can also target a very specific problem such as the establishment of a social protection system in drought prone agricultural areas with high poverty rates, drought-proof design of hydropower dams, or the placement of refugee camps. To ensure that any drought risk assessment undertaken provides useful output in the context of its specific purpose, it is important to consider several key principles when preparing and carrying out a drought risk assessment.

First, drought has to be defined and assessed in relation to its impacts.

Drought risk assessments have to start with an inventory of historical and potential impacts instead of focussing on the drought hazard. Which sectors and water users are exposed and vulnerable to droughts? These could include the drinking water sector, irrigated agriculture, hydropower dams, as well as small communities and pastoral farmers that depend on local rainwater. The water source that is used by the exposed and vulnerable sector or community under review determines what type of drought hazard needs to be analysed. For example, if the drinking water sector depends mainly on groundwater, drought characteristics related to groundwater recharge and groundwater resources need to be assessed. For an analysis of drought risk for small scale farmers that use local precipitation, an assessment of meteorological drought indicators could be most useful, whilst drought-proofing hydropower dams requires drought indices related to the runoff of (sub-)surface water of a river system.

Credit: Kees Sloff

Second, drought assessments should use a system-scale perspective.

Drought risk assessments should be carried out in correspondence to the appropriate spatial resolution and temporal scales for the impact sector under review. Choosing the appropriate system scale perspective depends strongly on the historical and potential drought impacts and vulnerable sectors exposed. For instance, small communities and pastoral farmers depend mostly on local water, while hydropower dams and drinking water reservoirs depend on the river discharge from the full upstream catchment area. In this context, it is of great importance to engage with all relevant local stakeholders, use local and international expertise, and build a shared knowledge base between experts and all involved stakeholders.

Credit: Adobe Stock

Third, drought risk changes over time.

Drought risk assessments targeting future adaptive planning and development of long-term solution strategies should account for climate change and socio-economic developments as they affect the occurrence and severity of drought risks in the future. Climate change mainly affects the characteristics of drought hazards (location, intensity or magnitude, frequency, and probability). Socio-economic developments relate to changes in land use, population growth, economic developments, and level of prosperity, which, in the context of drought risks, may change the level of exposure of sectors and water users as well as their vulnerability to drought. In some cases, the negative impacts of droughts are postponed because societies rely on groundwater resources in an unsustainable way. Several studies have already shown that groundwater reserves in aquifers around the globe are diminishing, implying that groundwater may be threatened as an alternative sustainable water source. As a result, future drought events with the same extent may have an even bigger negative impact on agriculture, urban water supply, and the overall economy.

Credit: Pablo Tosco, Oxfam

And fourth, effective drought management should increase resilience and enhance preparedness.

In addition to short term relief actions during or after drought events, it is important that drought management plans are in place that include well-organized governance mechanisms, clarify priorities in case of drought events and describe sector and area specific management objectives and action plans for each drought severity level. Furthermore, people-centred preparedness, early warning, and monitoring systems are crucial aspects of short- and long-term drought management plans. Effective drought risk assessments contribute to drought management plans or to specific actions that increase long term resilience and/or enhance preparedness for the specific areas and sectors at risk. It is important that such specific drought adaptation or mitigation goals are clear at the start of the risk assessment.

The new guidance document “Assessing Drought Hazard and Risk: Principles and Implementation Guidance” describes these principles in detail and provides key insights and considerations that can guide their implementation. We hope it will be useful for governments, development organizations and professionals as they work to build drought resilience in communities everywhere.

We wish to acknowledge our consortium of partners in developing the guidance document: Deltares, Applied Research Institute for Water and Subsurface; Institute for Environmental Studies, VU university Amsterdam; IHE Delft Institute for Water Education; University of California Santa Barbara; and National Drought Mitigation Centre, University of Nebraska.